How you feel after may depend more on how you respond than what happens

Before I do a race, I make a plan. For this particular 100m individual medley (25m of each stroke), it was as follows:

- Length 1 (Butterfly) – stay streamlined off the glide, maximise the underwater phase and stay relaxed for the remainder of the length.

- Length 2 (Backstroke) – push off hard and do seven underwater kicks. Swim strong, but not quite all-out

- Length 3 (Breaststroke) – powerful underwater pull and kick, max effort to finish the length

- Length 4 (Front crawl) – sprint!

Also, time my strokes for slick turns.

Blinded

In boxing, they say no plan survives being punched in the face. In swimming, no plan survives a goggles failure.

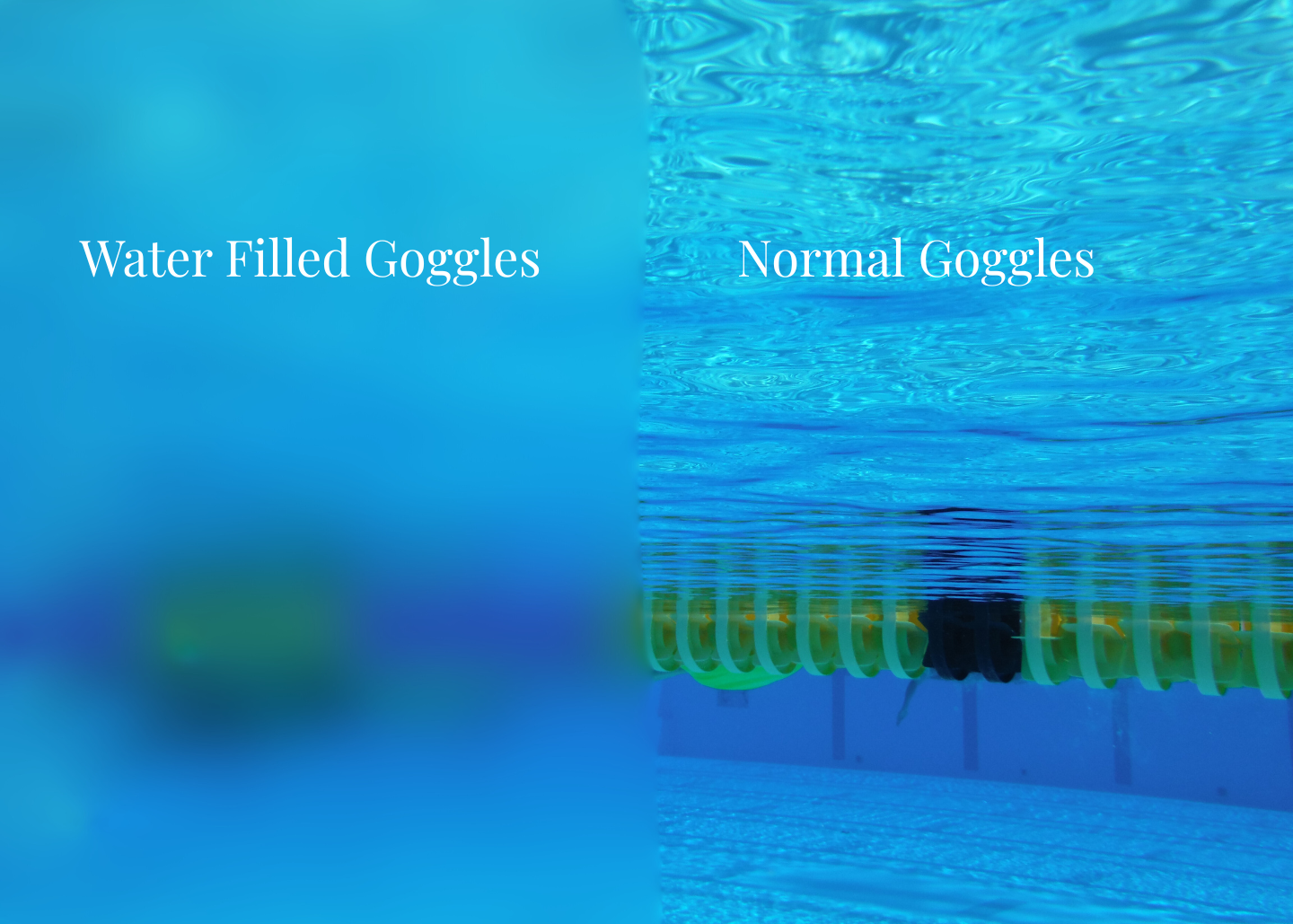

As I dived in, both lenses lifted from my face, filled with water and settled back into position. It was worse than having no goggles. I could barely see anything – either above or below the water. The only thing I could vaguely make out was a blurry impression of the black line along the bottom of the pool.

Stopping to empty my goggles wasn’t an option. Breaking your stroke on butterfly gets you disqualified. My choices were to give up or use this as a learning experience, and possibly something to write about.

Glide to survive

When the blurred black line ended, I knew I was near the wall, but I couldn’t see it. I took a final butterfly stroke and glided until my hands touched. I was scared about smashing my face into the wall, so I probably took one stroke fewer than I needed, but I survived the fly.

I was hoping for respite on the backstroke, but I couldn’t see the ceiling. In my warm-up, I’d noted the ceiling had nice straight lines to follow. Without being able to see those, I struggled to swim straight and quickly struck the lane rope. At least that gave me something to follow.

Counting strokes

In backstroke, we rely on the turn flags, 5m from the wall, to warn us when to turn. I couldn’t see those either, but I’d been counting strokes, which I only realised I’d been doing about halfway down the length. When I got to 17, I knew I’d be close to the end, so I kicked my way to the wall, one arm stretched ahead to protect my head.

I hit the wall sooner than expected and fumbled the turn – but I’d stayed on my back and hadn’t broken the rules. I was still in the race.

Breaststroke was the easiest. I tried to swim as normally as possible, although I suspect I held back a little, especially as I approached the wall again. Guided by the changing colour of the floor tiles, I glided and felt my way to the end, conscious that I needed to touch the wall I couldn’t see simultaneously with both hands.

Not so sprinty

Finally, on the front crawl, the length I intended to sprint, I once again found myself holding back. I know how painful it is to trap your fingers between the floats on a lane rope or hit the wall headfirst. I finished with a long, leisurely glide.

I pulled off my goggles and saw I’d finished comfortably last – but I had finished. My time was some three seconds slower than the last time I did this event, but I wasn’t disappointed. In fact, I was pleased with how I’d responded. I neither panicked nor got angry. I did the best I could in the situation I was in – a Stoic approach.

During the swim, I didn’t stop to ponder why this had happened. I just dealt with the situation. Figuring out what had gone wrong and how to stop it from happening again was a task for afterwards. I’ve swum and dived in those goggles many times without problem. I suspect I didn’t tuck my chin down enough when I hit the water. It’s possible I loosened the straps for a long-distance swim and forgot to retighten them.

When slow is good enough

For my next race, I tightened the strap and focused on getting my head in the right place on the dive. It went fine.

But the key thing I learned is that you can feel good about a swim, even when it goes badly. Although my time was slow, I had done the best I could, and that’s enough.

The experience has also given me a new appreciation of blind and partially sighted swimmers. It takes more guts than I’ve got to swim at full speed when you can’t see where you’re going.